Adverse Effects: The Perils of Deep Brain Stimulation for Depression

Hundreds of people have been given remote control deep brain stimulation implants for psychiatric disorders such as depression, OCD and Tourette’s. Yet DBS specialists still have no clue about its mechanisms of action and research suggests its hefty health and safety risks far outweigh benefits. Two device manufacturers recently pulled the plug on experimental clinical trials, leaving DBS recipients scrambling to find ways to pay for the necessary lifelong health care, seek medical specialists to take charge of the brain clicker, replace or explant malfunctioning hardware and manage a wide range of adverse effects.

By Danielle Egan

MIA Correspondent September 24, 2015

“I just want the thing out,” says Jim*. “It could be harming my brain and it’s certainly doing a lot of psychological harm to me. It’s a very real presence and I can feel the wires under my skull and at my neck. After two years of this, I just want to be done with it.”

Jim is talking about a deep brain stimulator, a remote control implant that delivers chronic electricity to the brain. Jim received the implant on June 2013, at UCLA, as part of an experimental clinical trial to treat severe depression. (Jim is a pseudonym, as he asked that we not use his real name.)

Globally, at least 272 people around the globe have received experimental implants to treat psychiatric disorders, according to a recent meta-analysis of published trial data of individuals with depression, OCD and Tourette’s syndrome. The trial that Jim participated in is called The Broaden Trial, a multi-center experimental device study that began in 2008, and at its peak included 128 patients at 15 different institutions in the United States. It was called Broaden in reference to both the large number of centers and participants involved in the trial, and the area of the brain where the implant is placed, the Brodmann Area 25, an almond-sized part of the cerebral cortex thought to be implicated in depression.

The experimental trial was sponsored by St. Jude Medical, a Minneapolis-based medical device company that specializes in heart pacemakers. The company was looking to expand its product line to include a neurostimulation device called “Libra.” St. Jude’s primary competitor, Medtronic, has had an FDA-approved DBS implant to treat essential tremor since 1997, for Parkinson’s since 2002, and under a “humanitarian device exemption” for dystonia since 2003 and for OCD since 2009.

However, since the Broaden Trial began, no device companies have received FDA approval for depression, though a handful of experimental studies have been conducted in Europe and North America for depression, OCD and Tourette’s syndrome. The Broaden Trial was scheduled for a year-long follow-up, and DBS recipients were invited to participate in an additional four-year follow-up study so that the sponsors could continue to investigate efficacy and safety. Participants enrolled in the followup trial would also receive continued monitoring and medical care by trial doctors, including so-called “dosing” changes to the electrical implant, and replacement of any faulty DBS parts, particularly the battery-powered chest “pacemaker,” which can run out of power in as little as ten months, necessitating replacement surgery.

The Procedure

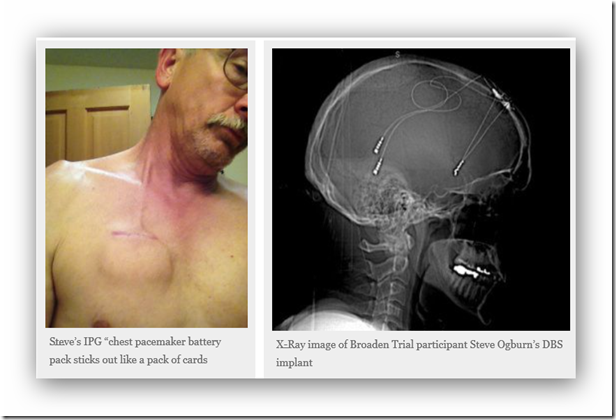

Insertion of the DBS device into Jim’s brain involved a complex day-long brain surgery at UCLA. To start, his brain was scanned with an MRI so that the specific target, also known as the subgenual cingulate gyrus (Cg25), could be anatomically located. Next, his head was shaved and a stereotactic frame was bolted into his skull to help the surgeon target the desired brain region for the implant. Then the surgeon drilled two holes through the bone in his skull, just above the hairline, and with a surgical cannula, inserted the device’s two spaghetti-sized wires--each attached to four ‘electrode contacts,’ all of which can deliver up to 10 volts of electricity--into both hemispheres of his brain until those electrode contacts, each measuring 1.5 millimeters, reached the anatomical targets. Then the two brain implants were connected to two sets of wires that were tunnelled back through the brain to the skin just beneath his scalp, and around the back of his ears and down his neck to his chest.

A second surgery in his chest was done to install an internal pulse generator under the skin, called a brain pacemaker because it serves as the electrical engine that delivers electricity via wires to the brain implant. The specific voltage for each of the eight electrode contacts are set by an external remote control computer programming device, the settings of which are controlled by a medical specialist.

The electrical implants aren’t turned on to provide chronic brain stimulation until two weeks after DBS surgery, which allows the brain to heal from the trauma of the surgery, which causes inflammation and brain shift of up to six millimeters. This “brain shift” results when impact to the head causes one lobe to shift beyond its midlines, pressing into the other lobe and the confines of the skull.

DBS surgery comes with a host of other potential surgical risks, including:

- up to an 8% risk of bleeding in the brain that can lead to permanent deficit, or death 1.1% of the time.

- an 8% chance of stroke or permanent neurological deficits.

- a risk of infection of up to 15%.

- 5% risk of hemorrhage.

- 2% risk of seizure.

- the potential for air to enter the brain, and leakage of cerebrospinal fluid or brain fluid.

‘Hardware-related’ complications are also possible (including breakage or migration of the implant’s wires or electrodes), all of which could necessitate additional brain or chest surgeries, including device wire fractures that make it impossible for the pacemaker to deliver electricity to the contacts in the brain.

Jim’s experience

The fact that Jim, a 48-year-old attorney, was willing to undertake such an invasive, complex and risky brain surgery illustrates just how desperate he’d become to find some method of curbing his debilitating treatment-resistant depression. “At that point I was in the midst of a severe episode of depression, the most severe I’d experienced,” says Jim. “It had all but completely shut me down. My psychiatrist is great and I had a lot of faith in him. We’d tried everything there was, over 40 different meds over the years, and nothing worked. I’ve also spent years doing cognitive behaviour therapy. I even did ECT in 2000 and I didn’t want to go through that again – the memory loss and cognitive issues were too high of a price. I had 26 ECT treatments and the result was significant memory loss; I don’t remember my wedding, September 11th. I didn’t want to do that again. So in 2013 my psychiatrist told me about the surgery. I thought, ‘Before I check out, I’ll try this – I’ve got nothing to lose. I never like to think of myself as actively suicidal but I didn’t think I’d come out of this one.”

Jim survived the surgery, and two weeks later, he returned to UCLA to have his first implant programming session. The trial was blinded for the initial six month duration, so that only one investigator involved in the trial knew whether Jim was in the active stimulation ‘on’ group or the ‘off’ control group.

“I thought I was ‘off’ because I had no benefit,” says Jim. “I was still struggling with depression and suicidal feelings.”

Jim also had a number of adverse effects that began post-implant. “I had severe mental fogginess, trouble reading, concentrating, focusing, doing my job—tasks I’d done before almost in my sleep. I had to apply for disability. I had a profound feeling of disconnection with reality, disconnection from the world around me, and anhedonia – that’s an inability to feel pleasure, motivation, anticipation, even from things you enjoy doing. I had some anhedonia before the surgery, but not to that extent. It was a lot worse after DBS. I felt very different, the changes felt internal – the innermost workings of your brain. I’d never felt like that before.”

The Theory of DBS

Proponents of DBS still have no idea about why DBS might provide a benefit, or its possible “therapeutic” mechanism of action, even though it has been researched since the ‘80s. Studies have described phenomenon that point to inhibition or enhanced neuronal activity, and excitation of brain cells. Tests have shown that stimulation at each of the four contacts, at one volt, can stimulate neurons and brain tissue two millimeters from the contact, and at a 10 volt setting, can stimulate neurons and brain tissues up to 6 millimeters away. For the Broaden trial protocol, Jim says that only the two middle contacts on each side of the brain were turned on during the trial to target the Cg 25 area as precisely as possible.

Whether Jim’s DBS was ‘off’ or ‘on’ and exciting or inhibiting his brain, he had no benefit from the depression. However, his adverse cognitive side effects—and similar adverse effects experienced by two other Broaden trial DBS recipients that I interviewed for this article—could point to an inhibiting effect, which was actually the initial rationale for DBS in depression. The effect is also reminiscent of the cognitive blunting experienced by lobotomy patients, which was introduced in the mid 1900s.

After a surge in popularity in the 1940s, lobotomy subsequently fell from grace and came to be seen as a mutilating procedure. However, psychosurgery—the destruction of brain tissue—never completely disappeared, and it went through a comeback phase in the 1990s, particularly at a handful of medical centers that have since become the primary proponents of DBS, implanting the device in the same brain regions targeted with psychosurgery. The primary objective with modern psychosurgery is to lesion the brain target by burning or cutting the brain tissue.

For depression, various parts of the brain may be targeted, including the cingulate gyrus, a part of the brain in the cerebral cortex just above the Cg25 area. DBS was assumed to be a better method for inhibiting activity than permanent lesioning, because the intervention is potentially reversible by removing the DBS device. But so-called “microlesions” from the surgery and the implant are also evident in DBS recipients. Long-term studies conducted with DBS recipients for Parkinson’s—so far more than 100,000 people, with an efficacy rate of approximately 50%—have also documented DBS-related scar formations in the brain. Numerous studies have also documented many serious adverse mood, behaviour and personality changes. These include suicide, depression, apathy, fatigue, mania and serious impulse control issues, such as hypomania, aggression, addiction (to gambling, shopping, drugs, alcohol) and hypersexuality, sometimes resulting in criminal behaviour, including pedophilia.

Moreover, the risks with DBS for psychiatric disorders are likely to be more pronounced than with Parkinson’s. With the latter disease, the brain’s movement centers are targeted with a DBS implant. But with DBS for psychiatric disorders, the targets are in the cerebral cortex, known as the brain’s CEO, because it handles a wide range of executive cognitive functions such as learning and sorting and rationalizing input from other parts of the brain and from the external world. The cerebral cortex is also known as the seat of personality, and has been linked to mood, behaviors, decision-making and impulse control.

The Broaden trial targeted a small area in the Brodmann region of the cerebral cortex, a vast network that governs sensory, visual and motor skills, along with a grocery list of cognitive, behavioral and mood-related functions. The specific target, the Cg25, has been linked to self-esteem, motivation, reward-based thoughts and behaviors and moral decision-making. It is also dense with neuropathways to other brain regions in the limbic system, a part of the brain that regulates emotions, memory and other autonomic functions (appetite, sleep, circadian rhythm), including the hypothalamus, the amydgala, the hippocampus and the insula. Clinical studies have linked tissue damage in the Cg25 with disinhibition, which is associated with frontal lobe brain damage causing poor impulse control.

Post-op PET brain scans done on the first patients involved in a pilot study investigating DBS of the Cg25 for depression (six people involved in a Canadian trial, the results of which were published in Neuron, in 2005) showed activity decreased in the Cg25, which was interpreted by these researchers as a positive inhibiting effect. Yet blood flow increased elsewhere, particularly the brain stem, where the body’s most crucial survival mechanisms are regulated, like heart rate and breathing as well as anxiety and euphoria. Other neuroscientific studies have linked these various blood flow changes to mania, dementia and serious psychiatric personality disorders including psychosis and dissociation.

Informed Consent?

The Broaden trial consent form included some information about potential adverse effects, but these were called “rare complications” in mood and personality, described as apathy, suicide, attention deficit, anxiety, ruminativeness, hypomania, mania, panic attacks, OCD and psychosis. Monitoring of these adverse side effects is crucial, though papers published by concerned medical specialists have criticized previous clinical trials for focusing almost exclusively on efficacy and neglecting safety issues and adverse effects reporting, or dismissing these negative effects as side effects of depression, particularly suicide rates. Broaden trial participants were required to visit the study center every two weeks for two months, then monthly for the remaining blinded four month period (to discuss any complications, do mood assessments and ‘memory/cognitive function’ tests, receive device programming changes to ‘optimize’ therapy). At six months, all trial participants started receiving stimulation and had monthly followup visits for a year. But during the long-term followup phase, a time when adverse effects often emerge, the participants checked in only once every six months.

Jim had no clue that six months into his trial participation, St. Jude Medical, the trial sponsor and maker of the DBS implant, terminated the trial after it failed to reach its benchmark of a 50% response rate according to the Hamilton Depression Scale. St. Jude released no public information about the trial’s termination (and still hasn’t), but the news was first reported by the editor of Neurotech Reports, in December, 2013, saying that St. Jude had made the an unofficial announcement about the trial’s termination at the annual meeting of the North American Neuromodulation Society. This is an organization of doctors and manufacturers of DBS devices, and also of business investors with an eye on the neuromodulation market, which is estimated to be $3.6 billion this year, and forecasted to grow by at least 11% by 2020.

When the blog “Neurocritic” posted a piece about the trial’s end, in January, 2014, a handful of Broaden trial participants posted their comments and concerns on the blog. Some had benefited from the DBS, while others reported serious adverse effects, but regardless of outcomes, all commenters expressed deep concern that they would be orphaned by the trial sponsors and by the medical specialists charged with their followup care.

Some additional insight about the trial’s termination came six months later, in an academic paper published in a July 2014 issue of Neurotherapeutics, authored by University of Florida College Of Medicine specialists in DBS. According to a letter from St. Jude’s clinical study team, a statistical futility analysis done after 75 patients reached the six-month post-op followup, predicted “the probability of a successful study outcome to be no greater than 17.2%.”

Media Hype Preceded the Blackout

The lack of public information provided by St. Jude is in stark contrast to the publicity that DBS for depression began generating in 2006, soon after the initial results of the Canadian pilot trial, which by that point included twelve patients, were released. A New York Times Magazine article titled “A Depression Switch” included amazing stories of recovery for eight of the 12 patients, along with quotes from the two primary investigators. Neurosurgeon Dr. Andres Lozano called the targeting procedure “quite easy,” and neurologist Dr. Helen Mayberg said that the surgery was “fixing the circuit” related to depression.

Doctors unaffiliated with the study were also quoted as praising the study results. “This just makes so much sense… the weight of the results is so sizable,” said Dr. Antonio Damasio, a University of Southern California neurologist. Meanwhile, Thomas Insel, director of the National Institute or Mental Health, suggested that a breakthrough in depression treatment might be at hand. “Here we know enough to say this is something significant. I really do believe this is the beginning of a new way of understanding depression.” The Times reporter also noted that “the treatment so far seems remarkably free of side effects,” citing only the potential for slight adverse reactions related to high dosages. DBS was hailed as an alternative to antidepressants for people that were so-called “treatment-resistant,” meaning that medications didn’t benefit them.

Confusion in the research literature

The long-term results of that initial pilot study, published in 2012, including 21 patients, saw the response rates plummet to 29 percent, and included “a large number of adverse events” including one suicide and one suicide attempt. Nine individuals had gastrointestinal issues like nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, six had headaches long-term, six had persistent pain, four had muscular issues like tremors, spasms and stiffness. Yet the researchers claimed that “none” were “thought to be the result of the stimulation per se,” but instead “likely related to the patient population.” They blamed the “disease,” rather then their treatment.

Results from several other long-term trials (of more than six months followup), and from randomized, controlled trials of DBS for depression, which were conducted in a number of countries and sometimes targeted other parts of the brain, have also yielded less than favorable results,, including a recent Massachusetts General/Harvard study that found DBS had no better efficacy than sham treatment, the surgery-specific method of testing placebo effect. That multicenter study sponsored by Medtronic, the biggest player in the DBS device market, was also terminated after it failed to reach the 50% improvement benchmark.

Two recently published study outcomes did report high efficacy rates of DBS of the Cg25 area in the brain. A Spanish group had response and remission rates of 62% and 50% respectively in eight patients (with a Medtronic implant) including one non-responder who became a remitter after being given post-implant ECT, even though the implant has never been tested in combination with ECT and Medtronic has a warning against that combination.

Helen Mayberg and her Emory University co-investigators have also reported results for their St. Jude sponsored trial. After one year, and a total of 14 patients, five patients were responders and another five patients were remitters. After two years of DBS, all 11 of 12 patients were considered responders, and 7 of those patients were remitters. The Neurotherapeutics paper by the University of Florida specialists called these reported outcomes “exceptionally good, adding that, “It is noteworthy that the currents delivered in this study [up to 10 volts, the maximum voltage] were typically higher than those in other reported studies.”

The University of Florida group has also written about the risks of high-voltage stimulation with OCD, which has been linked to adverse behavioral and mood changes including euphoria, hypomania, fear and panic. According to the Florida authors, “There is an urgent need for some expert consensus on the best approach to acute and long-term programming of OCD DBS devices…. the effects of electrical stimulation are much more complex than can be explained by simply stating they are excitatory or inhibitory; they also involve astrocytes, a propagating calcium wave, neurotransmitter release, and changes in blood flow… There is some concern that high voltage stimulation may result in the tissue damage though there is a lack of data on this point, and clinical outcomes to date have been positive. More research and perhaps post-mortem data may be helpful in clarifying this issue.”

DBS trial sponsors have also been criticized for substandard reporting methods. One 2013 meta-analysis of DBS for psychiatric disorders excluded 25 of 49 published medical articles, in part because the data didn’t include “standardized outcome scales” or had a “lack of statistical support that shows that DBS is an efficacious therapy for treatment-refractory patients.”Another 2010 paper published in JAMA, co-written by a neurosurgeon who performs DBS surgeries in Europe, stated the ethical issues quite bluntly. The authors wrote: “In 2004 the international committee of medical journal editors put forward a fundamental truth: ‘The case against selective reporting is particularly compelling for research that tests interventions that could enter mainstream clinical practice.’ There is perhaps no arena in medical research where the threat of selective reporting is greater than in the emerging field of deep brain stimulation and neuromodulation… this area is particularly vulnerable to bias because of an excessive reliance on single-patient case reports. Until cohort studies are routinely performed, the possibility will remain that only positive results will be published at the expense of negative data that might also have important implications.”

Another paper by neurologist Erwin Montgomery discussed many flaws in DBS research including confirmation bias and “the fallacy of confirming the consequence,” which Montgomery called “particularly problematic as it is the essence of the Scientific Method where hypotheses are tested and then modified if the experiments are inconsistent . . . . The resolution of the paradox often is “majority vote” when the contrary evidence is not ignored outright. This has the perverse consequence that a flawed experiment replicated a thousand times trumps a valid experiment done once . . . In terms of DBS science, the error is in studying one structure to the exclusion of others and then attributing the therapeutic mechanisms to the single structure studied. Even a cursory survey of the literature will demonstrate that the overwhelming majority of studies have been confined to the study of a single structure…. To date, hypotheses as to the mechanisms of action have been derivative from prevailing implicit presuppositions and explicit theories of pathophysiology, most of which are incorrect.”

Financial conflicts of interest

Given the problems with DBS research, and with growing evidence of bias in much clinical trial research conducted, it's perhaps no surprise that many of the doctors and specialists involved in these DBS trials were paid by device manufacturers and/or provided with research funding. For instance, among the investigators involved in the initial Canadian trial, Dr. Helen Mayberg holds patent and licensing rights for the treatment of depression through DBS of the Cg25. Neurosurgeon Dr. Andres Lozano is a consultant for Medtronic and holds intellectual property rights in DBS; in 2010, he founded of a DBS investigational company called Functional Neuromodulation, a partner company of Medtronic.

Back to the Broaden Trial

That initial Canadian pilot trial, which began in Toronto, based partly on brain scan research done by Mayberg in which she posited that the Cg 25 was linked to sadness in depression, expanded in 2006 to include Vancouver and Montreal centers, but the trial was then sponsored by ANS, a DBS manufacturer in the United States that has since been purchased by St. Jude Medical. In February, 2008, evidence from the initial Canadian pilot study (including the initial six patients implanted with the Medtronic device and 14 additional patients with the St. Jude device) seemed so promising that St. Jude Medical announced the kick-off of the multi-center Broaden trial, with three U.S. sites, in Chicago (at Alexian Brothers Behavioral Health Hospital), Dallas, and New York City.

Their press release boasted that their pilot study in Canada had a remarkable 78 percent response rate among the 20 patients, eight of whom “have re-engaged in life activities such as work, school, travel and relationships.” While a handful of other DBS-for-depression trials had already been conducted over the past decade around the globe, with various DBS device manufacturers, the Broaden trial was to be the first U.S. multi-center, controlled, double-blind trial. It was conducted under an FDA investigational device exemption, which allows sponsors to skip the standard phase 1 and phase 11 safety and efficacy trials, and has been criticized for putting patients at risk while facilitating corporate development (saving device sponsors millions of dollars). As the U.S. trial kicked off, St. Jude was also granted a U.S. patent to treat depression in the Cg25 with their “Libra” implant; the company president called the patent “a cornerstone in developing our approach to DBS for depression.” At that time, St Jude had no FDA-approved neurostimulation devices on the U.S. market to treat any diseases or conditions.

Jim was oblivious to all of these corporate influences and regulatory shortcuts. He was just trying to stay alive. Aside from the cognitive issues, he had extreme sleep problems that began about 6 months post-implant, a time when all trial participants started receiving electricity. “I’d have night terrors and catatonic sleep, like narcolepsy; it would just come over me in the middle of the day and I’d have 20 minutes to get somewhere safe before it took over and knocked me out; my wife couldn’t even wake me up. That happened four or five times per week.” Eventually Jim sought out a sleep disorder specialist who conducted a sleep study and diagnosed him with REM Behaviour Disorder, a condition in which the brain functions as it does during consciousness, and without the normal muscle paralysis that comes with REM sleep. The theory is that sleep and waking states invade each other and neurological barriers between states is dysfunctional. (Animal studies have found it’s caused by lesions in the brain stem where locomotion is inhibited.)

“The doctor discovered that for four to six hours a night I have no REM sleep, and the other half of the night I have three to four hours of solid REM sleep – the doctor said he’d never seen anything like that,” Jim says. “Who knows if it’s implant-related, or due to stimulation. I know it’s not related to medications because I wasn’t on any medications during the first year of the trial.”

Jim is an exception on that count. Post-implant, the significant majority of DBS recipients continue to take baseline medications, or start taking new meds, and while some published study results include detailed data on pre- and post-implant drug usage, no studies have been done looking at the potential adverse interactions with the combination of DBS and medications.

When the trial started, Jim was in the midst of a washout period in an attempt to try a new medication, but post-op, he was told that protocol dictated no change in meds for the one-year duration. “I found out later that other people were allowed to have their meds changed or tweaked, so I don’t think the study sponsors represented things accurately,” he says. His wife, a registered nurse, says, “It’s been so awful. He was so depressed during the blinded year. It was hard, just trying to keep him alive, painful for both of us, thinking this is our last hope and it’s not working. In fact everything’s become unbelievably worse. No [stimulation] setting worked.”

A short while ago, Jim returned to his study center and had the device turned off. “Now my thinking is clearing up a bit,” he says. “The fog is clearing a bit. The sleep problems have virtually disappeared. But I want this thing out.”

Soon, Jim will return to the neurosurgeon to discuss the removal of the device, but he’s worried about potential complications. “When I signed up for this trial, the consent form said that DBS is reversible because you can remove the implant,” he says. “But when I signed up for the followup study, the form had a different insert than the original consent form: ‘In some cases the device is not removable’ – where’s the evidence around that? I’ve read about the intracranial hemmorhage rates and that’s scary. There are so many nerve pathways just in that one region that connect to so many regions in the frontal cortex and the other parts of the brain. The surgeon said that the leads might be too tense and they might have to leave them there. When I enrolled in this trial, I was so desperate. But now that I’ve done more research and read all the extensive DBS literature, I feel I can’t believe anything I read. So much of it is vague and biased. And I found out that the Broaden trial is hiding behind an IDE [investigational device exemption] so it’s hard to get any info on what’s going on with the trial. The UCLA doctors have been great, especially since the trial was unblinded. But I feel as if there’s multiple levels of heresay when it comes to this technology.”

![image[18] image[18]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgKFCV6nAka-j27I7xZuN8gaKLdCziue38sBzlQ8TsjQOhPTW883h1S0qi5Td6gQyMYUCsg08nUZkt7wLiBdKnySYYjrqnbT9k51YA6CpAgVy0_WpCZEXI6i39kY945gB364AZh79YGoK4/?imgmax=800)

Back in 2008, Rich** had only read the glowing media reports about DBS. He was the second patient implanted in the Broaden trial that February 2008, in Chicago. “When I came out of anesthesia I was in complete remission from the depression,” says the 49-year-old who was working as a computer programmer for a large corporation at that time. “People at work were like, ‘That surgery did wonders.’”

That immediate post-op effect is called “the stun effect” and it’s linked to post-op trauma and oedema that decreases as the brain heals from surgery. “Gradually over the next six months, little bits of depression started coming in,” he says. “At six months everyone’s device got turned on. That’s when all hell broke loose with me. It hit me like a Mack truck. I was working from home doing a conference call and the rage just popped. Somebody said something stupid and I felt like I was going to murder someone. I called the [study] doctor saying, ‘I’m out of my mind.’ For the next 6 months that cycle repeated. I’d go in for programming, they’d change the [DBS device] settings to who knows what, they never said what they were doing, but within 24 hours, a new Richard emerged—apathetic Richard, manic Richard, suicidal Richard, homicidal Richard, who knows what kind of Richard would appear after these sessions.”

Rich says that when he reported side effects to the trial doctor, they would simply jot down a note and “throw a different drug at the symptom. Every month it was a new drug regime. I was on no drugs before the implant, but after the stimulation started, I was on a minimum of three drugs on average including antipsychotics. They didn’t say anything about side effects, just, ‘See you in a month.’ They’d also say things like, ‘You’re bipolar now.’ They’re telling me that, after four months of careful screening [pre-trial] and putting me in a treatment-resistant depression study? They didn’t even report side effects verbatim. I looked at my file and many things weren’t copied down. When I was in a homicidal rage, they wrote down ‘mild mania and anger issues.’”

Luckily for Rich and his sphere of friends, family and contacts, he only had three homicidal episodes, but they scared the hell out of him. These DBS-linked adverse changes had already been documented in Parkinson’s patients, and published in medical journals, but, Rich says, the study team “acted as if they had no clue why this was happening to me.” He describes these mood and personality changes as “emotional seizures” that would come out of nowhere and last up to three days. “It would be a single emotion, like rage, extreme anxiety, paranoia or self-harm. Between these episodes I was just a robot with no emotions, no feelings.”

Rich had to quit his job and go on disability. He signed up for the four-year followup study, which required visits with the study doctors once every six months. Rich will never forget what happened in August, 2009, a year and a half post-implant, and the day before his summer followup visit with the trial doctors. “I tried to lie down and sleep, but I couldn’t. I wasn't thinking about suicide. I wasn't thinking about anything. But then I got up, grabbed a sharp knife and started hacking at my arm. There was no thought behind my actions, no mental negotiation, no thought of consequences, no premeditation. It felt like an involuntary action, like my brain ordering my heart to beat. I remember being fascinated by the blood and understanding that since I was alone, I had all the time in the world. That’s when I got a call from the person at the [Broaden] study center, wanting to make sure I had the time and location of my appointment. I gave no indication of what I was doing until he asked me if I was safe. I just started laughing hysterically and couldn't stop. I eventually said something about being in a pool of my own blood. I guess the phone was handed off to another member of the study staff who kept asking me what I had done, what [part of my body] I had cut. Whenever she mentioned a spot, I’d cut that particular spot. Then she asked if I had taken any pills, so I started downing the bottle of Geodon [antipsychotics]. This went on until the police showed up at my door. I started to joke around with them. But that’s not like me to be disrespecting the police. I went for my bag where I had the wand [provided to DBS recipients to turn the device on or off by waving it over the chest pacemaker] and told them I had this brain implant, I just needed to get it turned off. But who’d believe that story? They carted me off to the hospital and then I was shipped to Alexian,” he says, referring to Alexian Brothers, the center conducting the trial in Chicago. The lead psychiatrist ,Dr. Anthony D’Agostino, was on vacation at the time. When he returned a week later, he signed Rich’s release forms and sent him on his way.

Soon after, Richard waved the wand over his chest and turned off the device. “At my next six month appointment I informed the study personnel that I had no intention of turning it back on until something was done to determine what was happening to me,” says Rich. He also tried to get the device settings changed, since a DBS device can be custom-programmed; each contact can be turned on or off and there are literally thousands of settings available. “They said, ‘We can’t change the settings. Only the voltage. We’ll just take out the implant.’ But I didn’t want that. This thing was the only hope I had left. I felt like they just wanted me out of their hair, that they just wanted to cast me aside.”

The following summer, Rich agreed to have the device turned back on, but only at its lowest voltage of 1 volt. “My reasoning was that since I was obviously hypersensitive to the device and it was magnifying, not suppressing, the activity in Cg25,” says Rich. “They argued that a low setting would be ‘useless’ but they agreed. The next morning I woke up in a state of total apathy, a total lack of emotion. My family and friends noticed it.” Rich was driving one night and was nearly involved in a serious car accident as a result of a dangerous driver, yet he had none of the typical physiological or psychological responses, such as increased pulse and blood pressure, sweating, fear or panic. That apathy lasted for four months and then Rich started experiencing what he calls “sadness bubbles” which he compares to carbonated bubbles rising to the surface and popping, but involving an intense feeling of sadness—“the saddest moment in your life suddenly pops into your mind and then disappears almost immediately,” he says. The apathy got worse over Christmas. While his family visited, he sat alone in the basement, feeling no guilt that he was avoiding everyone, or any emotion whatsoever. “I was devoid of empathy,” he says. “If the whole family had died, I would have just kept sitting there watching TV.”

Rich reported his side effects to the study center, but the only option they gave him was to have the device removed. That happened in February, 2011, three years after implant. But while the cognitive effects diminished slightly, he continued to experience bizarre episodes. “At that point I assumed the damage to my brain was permanent and it was. One night I was just sitting there watching TV. I got up, boiled a pot of water, poured it on myself, and went back to watching TV. It was like taking out the trash, just something you do almost automatically, without thought.” Eventually Rich went to the hospital to get the burns treated. “I see the scars every day, and I remember exactly what happened that day. But I don't understand how or why it happened.”

After the device was removed, Rich says that the trial doctors had promised that they would help him find psychiatric care, and they did, but after the self-harm episode, the psychiatrist refused to see him, saying he was treatment-resistant and there were no options left for him. “I’d give anything from a diagnostic look at what’s going on in my brain,” says Rich. “It would be so much relief to get a brain scan, even if there was nothing they can do about it. But I’d need a referral and I don’t even have a GP right now. I wrote an email to [Helen] Mayberg, saying, ‘You’re involved in studies of DBS effects. So, study me. There are people falling off the boat and you’re not circling back to rescue them. Circle back and see what’s going wrong.’ I didn’t hear back from her.”

Rich did correspond with a neuroethicist named Frederic Gilbert, who studies DBS at the University of Tasmania and has papers related to DBS side effects. Gilbert ultimately published a paper about DBS for depression in a 2013 issue of Neuroethics subtitled “Postoperative Feelings of Self-Estrangement, Suicide Attempt and Impulsive–Aggressive Behaviours.” He analyzed data from four North American DBS-for-depression trials that had published data (including two targeting the Cg25, one targeting the ventral capsule and one the nucleus accumbens), and he found that 9% to 11.7% of trial participants ultimately attempted suicide and the same percentage of patients committed suicide. That’s three to four times higher than the best estimates of a 3.4% suicide rate among people with severe depression. Rich’s grizzly suicide attempt was included in the paper as a case report of post-op suicide and “self-estrangement.” Rich has also communicated with other DBS trial participants, including an Amsterdam man who eventually committed suicide. He says that during a follow-up visit to his study center, he met another Chicago patient and he says that she had a negative outcome, too. “Where’s everybody else?” he wonders.

Rich is still dealing with severe depressive episodes, but it feels like an autonomic response, like an automatic gear shift on a car, except that his foot is never on the gas. “Before DBS I was the protagonist,” he says. “I’d ruminate and play the role of my [abusive] grandfather and tear myself down. I don’t do that anymore. I went from having an environmental depression related to my life experiences, to this state where my brain dictates how I feel. Now my whole mental health status is built on the biology of my brain. I can’t make myself depressed, but I can wake up tomorrow and be manic or suicidal as hell, for no reason. When the depression used to get bad, I wanted to kill myself, but since the DBS, when I have the suicide episodes, it’s like I have to kill myself. It’s as if I don’t have a mind anymore, I’m just a brain. My brain now controls itself. I work with every fiber of my being, to still be here. Otherwise I’d kill someone or myself, but it’s exhausting. I’d go back to my old severe depression in a heartbeat. Now I look at myself in the mirror and I wonder, ‘Who are you?”

Rich has many issues with the way the trial was conducted, particularly the lack of follow-up medical care, but he has no bitterness towards the neurosurgeon who performed the DBS surgery. "Trailblazing can be an exciting and noble endeavor,” he says. “But only if you're the blazer, and not so much if you're the trail."

The Neurosurgeon’s Perspective

According to a 2013 survey of 106 North American functional neurosurgeons, 82% said their primary patients are those with movement disorders, while 34% said that the majority of their patients had psychiatric conditions primarily with OCD and depression. Ninety percent of these surgeons felt “optimistic about the future of neurosurgery for psychiatric disorders.”

Dr. Konstantin Slavin, who implanted Rich and all of the 20 Chicago trial participants, is one of the enthusiastic ones. “This is a very exciting time to be doing research,” he says. “The Toronto studies were very impressive and it’s why I bought into DBS of the Cg25 as a viable treatment for depression.”

The majority of Slavin’s patients have Parkinson’s, and that surgery involves intraoperative stimulation while the patient is awake, to test for specific targets that help curb the debilitating tics. Neurosurgeons have also done this with depressed patients and found that they can elicit intense positive and negative emotions, specific memories, cravings for food or sex—you name it—by test-stimulating parts of the brain. “But the Broaden trial was blinded, and because of that, our patients were unconscious and we didn’t test stimulate for emotional effects,” says Slavin. He also acknowledges that precise targeting is a challenge. “The Brodmann areas are not even visible on imaging studies and the Cg25 isn’t a well-defined area; it’s a pretty large area and every patient is slightly different. Also the brain is asymmetric in many ways, so the anatomy of cortical surface varies from the left to the right.” During surgery, Slavin targeted the Cg25 via other better-defined landmarks, particularly the ventricles. “The Cg25 target is so new for us and we didn’t know what to expect,” he says. “But in principle, the surgery is very straightforward. There will be micro-lesions from us sticking the device in the brain and manipulating it. And when you open the head, spinal fluid leaks out. Brain shift from the drilling process is also a concern, so we do intraoperative brain scans. But I didn’t see any surgery-related adverse effects—we were lucky.”

When I turn the talk to past trailblazers, such as Walter Freeman, the icepick lobotomist (who was a neurologist, not a surgeon), he says, “Freeman is still a great example of a doctor who had good intentions and wanted to cure humanity of a terrible disease.”

Electrical brain stimulation (EBS) also has a checkered past. Tulane University researchers, backed by CIA and military funding, did deep-brain EBS experiments on psychiatric patients and prisoners from the 50s until the 70s and reported that some patients “brightened” and experienced “warm and pleasant” sensations; others were driven to suicide. Their most infamous experiment involved trying to change a homosexual man’s orientation by rigging him up to electrodes and stimulating areas implicated with pleasure while he had sex with a prostitute. Jose Delgado was probably the technology’s most famous proponent. He famously stopped a bull from charging by stimulating its brain and he performed Clockwork Orange-style experiments on humans at Yale in the 1940s to cure aggression and schizophrenia, stating that “man does not have the right to develop his own mind,” and suggesting that EBS would “conquer the mind” and create “a less cruel, happier, and better man.” “Delgado did some crazy things,” acknowledges Slavin. “Nowadays, we’re careful not to repeat history and we’re better at the ethical protocols and patient selection.”

Slavin admits that depression is a condition that he knows little about, both in his life and in training. “We didn’t get that kind of training in school. What causes depression? That’s a deep question and something I can’t answer. Until I started doing these procedures, I didn’t realize that depression can be so severe. These people have tried hundreds of treatments. But I can say that about 20% of our patients got better. And all of them would get worse without DBS. Even if one person gets better, that’s worth it. The adverse effects profile is really benign—just turn it off if it doesn’t help. I don’t recommend explant. It’s an outpatient procedure but there are still risks, such as lesions, infection and bleeding. We’ve done a few explants, but I recommend to leave it in there.”

In terms of the mechanism of DBS, whether it inhibits or excites neurons, Slavin says, “I think it’s a bit of both, but in general, it’s a normalization.” While other neurosurgeons are trying DBS experimentally for Alzheimer’s, addiction, obesity, anorexia, bipolar disorder and aggression (and it’s even been suggested to treat criminal behaviour), he’s not worried that DBS will be misused for financial motivations or for off-label conditions. “There are so many surgical candidates for DBS,” he says. “My job security is pretty high. You can spin this story in so many ways. You should make it optimistic, so that it doesn’t make people depressed.”

Dr. Anthony D’Agostino is the lead Chicago psychiatrist in the trial. He says that of their 20 patients, perhaps five to seven people plan to keep their devices turned on post-trial. “Several people got worse and three or four were explanted,” he says, but for any additional information about the trial data, he directs me to speak to St. Jude Medical. I contacted Justin Paquette in its media department, who asked me to send a list of questions, and while waiting for a response, I contacted Dr. Mustafa Husain, the lead trial psychiatrist in Dallas. “Some of my patients could be poster children for DBS,” he says. “They’ve had remarkable life changes. One ob/gyn had quit his practice and moved to Mexico. Since the DBS, he’s back in practice. Of course there are non-responders, too. I’ll put you in touch with both.” When I contact him again in mid-June to be put in touch with patients, he tells me I have to go through St. Jude, but adds that some patients are still receiving follow-up care in Dallas. “We don’t leave them without any follow-up. Our center still has the programming devices and a few patients have been in to change their settings. When the follow-up wraps up, which should be within a month or two, we’ll send the programmers to the patients’ local doctors, ideally neurologists. They’ll get TAU (treatment as usual) and bill it to their insurance companies.”

Left to Foot the Bill

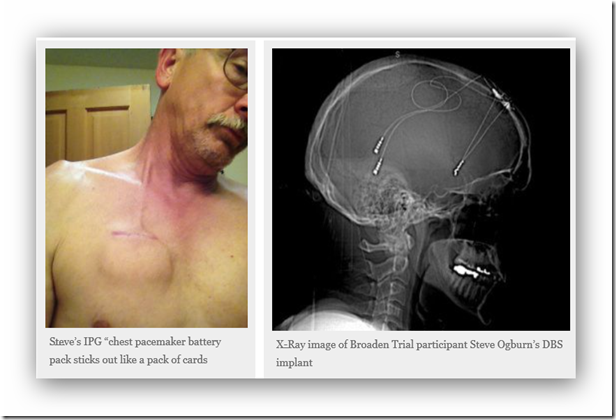

Steve Ogburn’s insurance company, like many insurers, doesn’t cover DBS for experimental, non-FDA approved conditions. But the 60-year-old California architect believed what was written in the informed consent document, which stipulated that all DBS-related care would be provided by St. Jude Medical, along with all “services, supplies, procedures and care associated with the study” that “are not part of routine medical care” including all “medical complications,” and “an injury or illness that is directly caused by your participation in this study, care will be provided to you. You will not be responsible for any of these costs.” The document also stated that medical care would “continue until the DBS system is approved by the FDA for the treatment of major depressive disorder, ANS [now St. Jude] discontinues this study or the FDA denies approval of the DBS system, whichever occurs first.”

Steve had the surgery at Stanford, in November, 2012. After the surgery, he had “severe cognitive decline” and a slew of physiological adversities. “The leads [wires] were 18 inches longer than they needed to be, so they coiled it up in the chest and at the top of the head; I could feel them externally,” he says. “And the leads were too tight. I could move my ear and my chest would move, too,” he says of a condition called “bowstringing,” whereby scar tissue encapsulates the wires (partly from the body’s natural response to foreign material), which has been documented in DBS cases and can cause permanent complications. Steve also had many symptoms that were ultimately diagnosed as shoulder and jaw muscle atrophy, spinal accessory nerve palsy and occipital nerve palsy. He reported all adverse effects immediately and continuously throughout the first year of the study, but the trial doctors continually told him that they’d never heard of such symptoms with DBS, even though nerve damage and DBS wire-related “hardware” complications were among the potential risks listed on the informed consent document.

“Even when there’s scientific literature published about these adverse effects, you’re constantly being told, ‘This is all in your head,’” says Steve, who didn’t want to give up hope that the DBS might provide therapeutic benefit, but he wanted to find out the root cause of his overwhelming pain. Instead, he was referred to Stanford’s pain clinic and provided numerous painkillers, but he didn’t receive the official diagnoses listed above until the following October, almost 11 months after implant. “The neurosurgeon, Dr. Henderson would only agree to a partial explant of the leads,” says Steve. “And then, if my pain had resolved adequately, he’d do another surgery to tunnel the leads down the [other] side of my head and neck, install a new IPG [chest pacemaker] in that side of my chest and reconnect them to the electrodes in my brain.”

Steve was very disheartened by the thought of at least two additional surgeries that might not provide any benefit, and could make his pain worse, so he chose the only other option available and had the entire DBS device explanted in December 2013, the day after he was told that the Broaden Study had been terminated. “The pain was even worse after the explant. At my eight week follow-up, Henderson said, ‘I’ve never seen this with over 1,000 DBS procedures—congratulations, you’re one in 1,000.’” That day, Henderson acknowledged that his many adverse effects may have been from the DBS wires pressing on the nerves, or that a nerve may have been “nicked” during the initial implant surgery. “After that, Stanford cut the ties with me,” says Steve. “But it was much worse than that. I was stonewalled by Stanford, St. Jude and the FDA. I participated in this trial in good faith that Stanford would cover all medical costs and that the FDA had oversight of the study.”

Steve sought help from a number of neurology specialists, but few would agree to take him on because his medical file included a notation that said he was “under risk management” as part of a research study. To pay for his six digit medical bills, he’s had to use his retirement funds, and after speaking with dozens of lawyers that wouldn’t touch his case, he found a lawyer through the Alliance for Human Research Protection. With his lawyer Alan Milstein, Steve is pursuing a lawsuit against St. Jude Medical, Stanford, Stanford’s IRB, and the neurosurgeon Dr. Henderson, alleging medical and professional negligence.

I contacted St. Jude and Stanford for their comments on the suit, but neither would provide comment “on pending litigation.” Steve sent me Stanford’s legal response, a “motion to dismiss” the case, stating that that the Stanford doctors provided appropriate care to trial participants under the FDA requirements for informed consent and medical care, which are regulated by federal courts—“matters that rest within the enforcement authority of the FDA, not this [state] court.” Regarding the IRB, the motion stated that “Stanford’s IRB is immune from liability under California’s Peer Review Statute Civil Code.” Also, under state law, Steve was required to begin legal action within a year of injury. That happened within two weeks of the surgery, and he reported the side effects, not just to the Stanford trial doctors, but also to other DBS specialists, including email exchanges with Dr. Helen Mayberg (the neurologist with the patent on DBS for depression). But Steve wasn’t given an official diagnosis and treatment options until a month before the statutory period lapsed and not long before the trial was terminated.

“In the three plus years I have been dealing with the effects of this clinical trial, only one doctor, Jeffrey Tanji, at UC Davis would see me,” says Steve. He ultimately had some benefit from scar revision surgery and orthopedic rehab. But the combination of chronic pain, chronic cognitive issues and what he describes as implant-related “depression on steroids,” makes it hard to simply put one foot in front of the other every day. Steve finds the legal battle exhausting, particularly “revisiting the deep, dark periods of despair” throughout the trial period, but he hangs to hopes that at his next court date, scheduled for October, a judge will reject Stanford’s motion to dismiss so that the discovery process might shed some light on the mechanisms of FDA-sponsored experimental trials. “My primary goal is better protection for humans in trials,” says Steve. “There’s no PETA for human lab rats. There’s more activism for death row inmates. I feel like I’ve been left twisting on a hook for two years. It’s like all of us Broaden trial participants have gone down a rabbit hole and all we can do is fingernail scratch on the walls.”

Steve keeps in touch with other DBS for depression recipients, in a private Facebook group of approximately 15 people, mostly participants in the Canadian trial and the Broaden trial. He believes that only one Broaden trial participant in the group has had some positive effects; the rest have had many adversities, including a person who recently attempted suicide. Since clinical trial sponsors aren’t required to publish study results, and even when they do, they rarely provide information about so-called “non-responders,” Steve has this profound question: “Who’s going to know the results of this trial? Who’s going to know our stories? The bigger story here is the need for protection of human participants in medical trials and real, transparent oversight from the FDA. It is so morally, ethically and legally wrong to not treat human participants with the respect and dignity we are owed. Our participation in this clinical trial has to have meant something.”

A few weeks after sending my questions to St. Jude Medical, I received a written response to some of my queries about the Broaden trial, via Paquette in the public relations department, providing the basic information about the total number of patients implanted (128), along with a statement about why the trial was terminated: “based on a low probability for future success.” Paquette wouldn’t provide any other trial data information, but he said that a paper was currently being drafted so that the details could be “disclosed in a future publication,” but that “this study was not terminated based on safety. There were no unanticipated adverse events recorded.” Regarding details on whether patients would be provided medical follow-up care for a specific duration, he would only say, “SJM has been continuing to support all implanted patients through a long term follow up protocol.” To the question of whether SJM was currently involved in sponsoring any other DBS trials for psychiatric conditions, he said, “SJM currently has one ongoing study in Canada for the treatment of depression. We support independent grants that are investigating DBS for depression [by providing] research grants to support physician-initiated trials investigating DBS for depression.”

This summer, SJM did receive FDA approval of their DBS device for Parkinson’s and dystonia, based on two clinical trials involving 136 patients and 127 patients respectively. That should give a big boost to their net sales, which climbed 4% in a year, to $5.622 billion ($437 million of which came from sales of their neurostimulation products), and their operating profit increased to $1.15 billion. Their legal costs have also increased from $16 million in 2012 to $31 million last year; according to their annual report “such proceedings could have a material adverse effect on consolidated results of operations, financial position and cash flows of a future period.”

The day after Jim’s explant surgery, he is in bed, recovering from a four-hour surgery that was scheduled as a routine one-and-a-half hour outpatient procedure. “I guess the surgeon had to do a bit of prying,” he says. “After he took off the burr caps that cover the holes in my skull, the second piece that fits into the skull gave him trouble because the bone and tissue had knitted around it. My head is throbbing around the burr holes and so is the skin around the [chest pacemaker] box. Hopefully it’ll all heal. I can’t go back and unring the bell. I feel like the DBS broke my brain; it broke something in me. I think the UCLA investigators did what they could for me, but I think that the way these studies are conducted, peoples’ health and safety is often secondary to the goals of the corporate sponsors. But I need to put what happened behind me. I’m just relieved it’s out.”

I don’t want to tax Jim’s head with too much future-gazing, but every time I try to get off the phone, telling him he needs to rest his head (mind, brain and all) from the operation, the conversation drifts into new territory, such as finding better methods to deal with depression, both medically (with better preventative measures and non-invasive treatments) and with greater cultural acceptance that depression happens in life, just like broken bones. Jim’s so smart and well-read and has such a great sense of humor that he cheers me up many times, until the conversation drifts into doctor-assisted suicide. “Let’s not go there today,” I say and then I tell him I’ll call back in a few weeks. He says, “If I’m not around next time you call, don’t be upset, OK?”

Steve made this video last year to inform the public about the perils of DBS clinical research

* Name has been changed at his request

** Surname not included at his request

*******

Danielle Egan is a Vancouver-based freelance journalist. Her articles about psychiatric neurosurgeries and bio-medical technologies have been published in many titles, including New Scientist, Vancouver Magazine, The Tyee, Jane and The San Francisco Chronicle.

Danielle Egan is a Vancouver-based freelance journalist. Her articles about psychiatric neurosurgeries and bio-medical technologies have been published in many titles, including New Scientist, Vancouver Magazine, The Tyee, Jane and The San Francisco Chronicle.

https://www.madinamerica.com/2015/09/adverse-effects-perils-deep-brain-stimulation-depression/

![image[18] image[18]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgKFCV6nAka-j27I7xZuN8gaKLdCziue38sBzlQ8TsjQOhPTW883h1S0qi5Td6gQyMYUCsg08nUZkt7wLiBdKnySYYjrqnbT9k51YA6CpAgVy0_WpCZEXI6i39kY945gB364AZh79YGoK4/?imgmax=800)